Preface

A CTF (Capture The Flag), is an event in which multiple teams will compete around different cyber-security challenges in order to win points. There are multiple types of CTFs :

- Jeopardy : Couple of tasks, arranged in categories. Each task gives points when solved.

- Attack/Defense : Every team has its own network with vulnerable services. You gain point by either defending your infrastructure and/or attacking other team’s infrastructure.

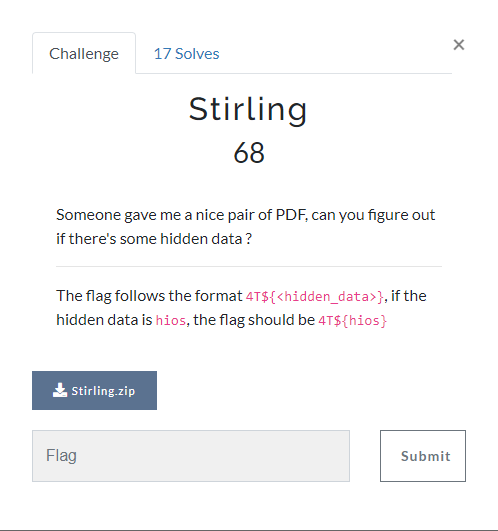

For a Jeopardy-style CTF, tasks can look a bit like this :

The challenges categories are usually the following ones:

- web: focuses on web application vulnerabilities, such as SQL injection, XSS, CSRF, and authentication issues.

- crypto: involves encryption, decryption, hashing, or breaking cryptographic algorithms.

- rev: involves binaries to understand and manipulate software behavior or recover hidden information.

- forensics: require analyzing data from various sources, like network packets, memory dumps, or file metadata, to extract information.

- pwn: focused on low-level vulnerabilities in binaries, such as buffer overflows, format strings, and memory corruption.

- misc: Unique or creative don’t fit neatly into other categories, often requiring unconventional thinking.

- steganography: focused on hiding and revealing information within media files like images, audio, or videos.

- osint: require finding public information on the internet using open-source resources.

Now, to add more context, I am one of the co-founder of 4T$ (a CTF Team) which is basically a group of two people.

We started participating seriously in CTFs in May 2024 starting with Punk Security DevSecOps Birthday CTF.

Fast forward to August and a brief conversation about creating our own CTF, and here we are, four months later, with our event officially complete (and ended).

And of course, this is also my first blog post, and it might be a bit disordered, I suggest you refer to the table of content in order to find what you’re looking for :D

The Project

Our goal might seem straightforward: we wanted to create our own CTF and hold it before 2025 (a personal challenge, I guess?)

And for our challenge, we had multiple goals in mind:

- Ensuring each player had an isolated challenge instance (one website per player);

- Maintaining zero downtime throughout the CTF, with no platform issues or instance outages;

- Having a secure infrastructure (foreshadowing?);

- Being original in some way.

Of course, we had to find at least one person (because neither of us two wanted to do a CTFd frontend) to create a CTFd theme.

«But wait, what’s CTFd ?» - one might ask.

Simply put, it’s a piece of software that allows anyone to handle the CTF players and submissions.

Their documentation is located on their website : ctfd.io

You can also choose to host your CTF on their servers, which is basically the easy way (which also comes at a cost)

We chose not to create our own “CTFd” for this event to save us [a lot of] time and probably headache as well.

Management

When it comes to project management, I only followed an online class, so that was a also a fun part of the challenge (even if we were only three with a lot of work).

Since I probably had the most motivation for the longest time, I also had to manage the project and follow up on tasks we set out to do.

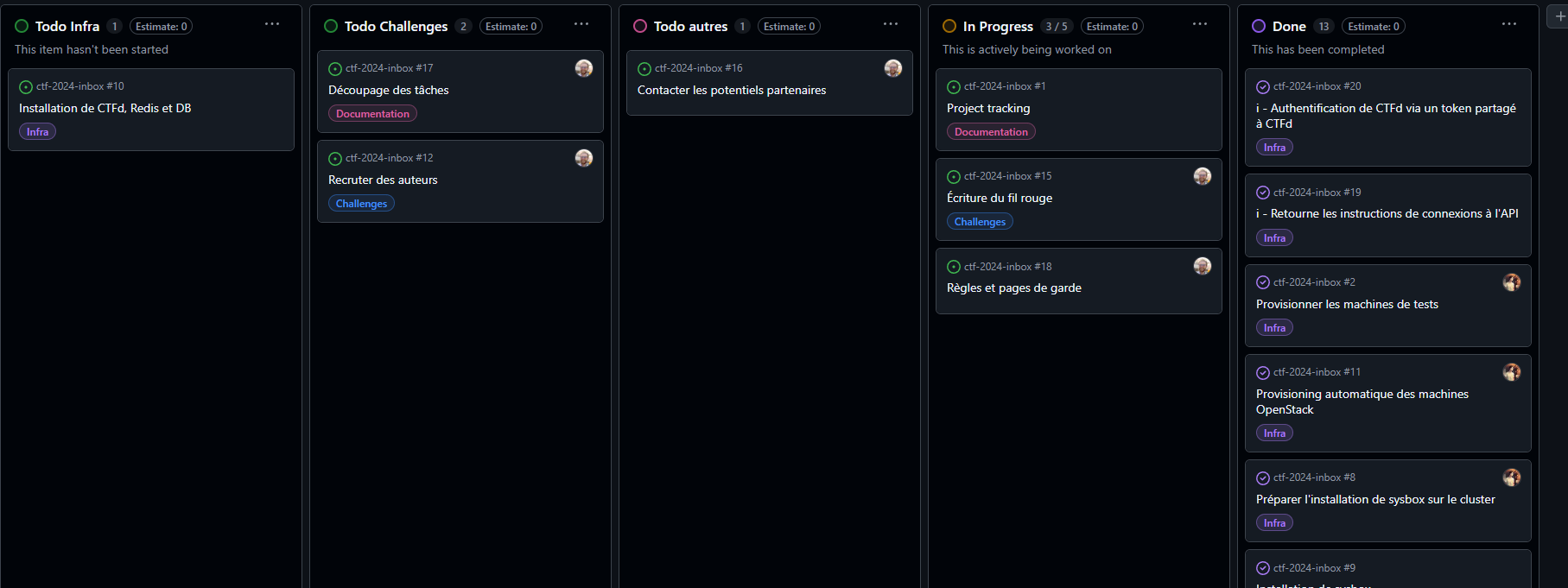

To do that, we set up two boards («why?» : explained later on) using Github Projects :

To keep organized, we also had a “Project Tracking” issue, that allowed us to keep track of what was said during meetings and what was left to do before the next meeting.

Meetings were erratic and mostly when we felt we needed to talk some things and also when we felt that a long time has passed since the last one.

What I felt was that the scariest part about managing is not knowing what people are working on (or not) for a certain amount of time.

Which is exactly what happened to me when we were working on the challenges:

Early on we decided to ask for a friend’s help to work on challenges of the pwn category, and I also asked a few other people for web challenges, crypto challenges, rev challenges, blockchains challenges, docker challenges and misc challenges.

In total there was 9 other persons helping us and it added a lot of mental stress especially during the last few weeks, which is when [most] actually started working on their challenges (including me).

This is definitely going to be improved upon in the next edition.

Timeline

Early on, we decided on a general timeline :

- Create an instancier (to handle challenge instanciation);

- Create a reproductible infrastructure (to keep it low-cost);

- Create a first challenge as a PoC;

- Test out our infrastructure + instancier on someone else’s CTFd;

- Create real challenges;

- CTF.

Somewhere in between this we also had to find sponsors for the event.

We managed to find our test environment very easily : in September, our school’s “first year’s” CTF took place and we just asked them to let us host one challenge (namely : kall)

the name :

kallcomes from the wordchall(chall-enge) but pronounced with a ch’ti accent (where ch ⇔ k).

Sponsors

The main sponsor of the event was Infomaniak, which is (coincidentally) the company which I work for. They gave us everything we needed : awesome prizes for the players, and more than enough credits to operate the CTF and even run our test run. We’re really thankful for the opportunity they gave us !

As a second sponsor, we managed to contact Offsec and get a few more prizes for the winning teams !

Infrastructure

I’ll begin with the infrastructure because it is the lowest level we’ll reach and explains things that will be useful later :D

Our main goal with the infrastructure was to tinker around Terraform to have a reproductible infrastructure for both our test run (which also acted as a validation) and for the CTF event.

Infomaniak’s Public Cloud relies on OpenStack, which (neatly) has a Terraform connector.

Our infrastructure is (or will be) public and contained the following :

- Uploading SSH Key to OpenStack

- Configure network with a main router

- Create the security groups for control planes and workers communications

- Create the control planes VMs

- Create the workers VMs (which had a special script at boot)

- Create the load balancer VM (for the control planes)

- Create the cluster thanks to K0S (which has a terraform connector)

- Setup CRI-O on the workers and reboot them

- Install FluxCD on the cluster

- Install the Cloud Secret on the cluster

During this setup we also export the administrative kubeconfig file to allow further configuration.

After this we can easily install what’s missing with Flux :

- Cert Manager, to manage the cert (duhhh);

- Cinder CSI, to manage volumes on OpenStack;

- Cloud Controller Manager, which manages Load Balancers in the cluster and create Load Balancers on OpenStack (ie. automagic network config);

- Monitoring (kube-prom-stack) to easily monitor what’s going on.

- Sysbox

This basically allowed me to create a fully functionnal cluster in about 20 to 30 minutes.

In the world of containerization, one key factor is that the container shares the same kernel as the host, this is also the main reason why containers are so fast to create (unlike VMs). Sysbox is a container runtime that aims to isolate your workload from your machine’s kernel by simply virtualizing more stuff than a regular runtime would do.

As an added bonus, Sysbox also enables you to run ANY workload. So if you want to run a sysbox container INSIDE a sysbox container, go for it (though the Dockerfile might get ugly at some point)

We’ll get back to Sysbox at a later point when we’ll talk about weird Dockerfiles.

If you want, you can access the repository that describes our infrastructure.

Instancer

Our instancer (namely : i [yes very original, much fun]) was initially a fork of klodd which I saw was being used in a CTF I enjoyed participating in.

How it works

Currently, the project lacks a proper documentation (as we did not have much time) but is, in essence, absolutely not like Klodd.

i is a Kubernetes Operator that allows us to define new resource into the Kubernetes Control Plane, we chose to define four new resources :

- Challenge

- InstancedChallenge

- OracleInstancedChallenge

- GloballyInstancedChallenge (not used in our case)

Challenge

A Challenge is basically described by what it looks like on CTFd, a name, description flag and such.

Here’s the example that corresponds to the challenge shown earlier :

kind: Challenge

metadata:

name: misc-stirling

spec:

name: Stirling

category: misc

description: |

Someone gave me a nice pair of PDF, can you figure out if there's some hidden data ?

---

The flag follows the format `4T${<hidden_data>}`, if the hidden data is `hios`, the flag should be `4T${hios}`

initial_value: 100

value_decay: 2

minimum_value: 50

flag: '4T${heyJSPDFEmb3d3d}'

files:

- name: Stirling.zip

path: Stirling.zip

repository: git@gitlab.com:4ts/ctf-2024/misc/stirling

state: visible

type: i_dynamic

decay_function: linearThis specification, allows i to synchronise with CTFd, which enables us to describe the state of our CTFd challenges with “easily” readable and reviewable files !

We also added some helpful features :

- Specify hints

- Specify files from git (

iwould then upload them to CTFd by itself) - Reference other challs (we ended up not using this, it’s basically to lock a challenge until another one is solved)

An enormous lack in here is the lack of a reference to the author, which CTFd doesn’t have support for, again, this will definitely be improved upon as well ! (authors can still be found if you search on the repos of the challenges)

InstancedChallenge

InstancedChallenge are basically the same, but also describe how the instance should work, for the most techies reading this, it contains the previous informations + these :

pods:

- name: main

ports: # These corresponds to the service that will be populated

- port: 8080

protocol: TCP

egress: false # Allow or not communication to Internet

spec:

runtimeClassName: sysbox-runc # Use our special runtime

containers:

- name: main

image: registry.gitlab.com/4ts/ctf-2024/web/are-you-sane:0.1.0

env:

- name: FLAG

value: '4T${7h15-f1l3-W45-N07-h1DD3N}'

resources:

requests:

memory: 10Mi

cpu: 10m

limits:

memory: 20Mi

cpu: 20m

automountServiceAccountToken: false # Very important !

imagePullSecrets:

- name: registry-4ts # This never changes

exposedPorts: # These are accessible by the player

- kind: http

pod: main

port: 8080

description: Web Interface

timeout: 1200 # How much time should the instance live (in seconds)

registrySecret: # This never changes either

name: registry-4ts

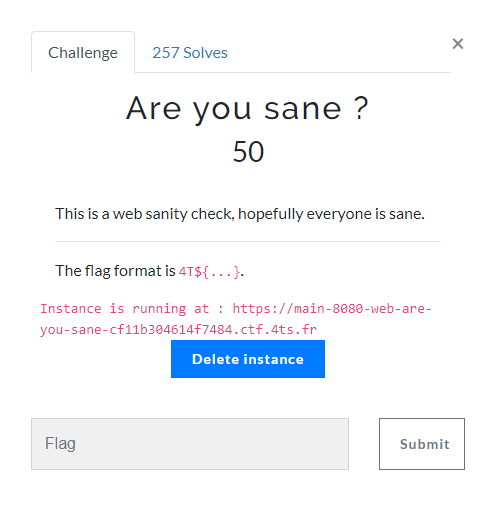

namespace: defaultExposed ports correspond to what’s going to be accessible to the player, you can define HTTP ports or TCP ports which are going to be exposed differently. Here’s what it would look like on the default theme :

Routing-wise, HTTP is fairly straightforward :

- client asks for a website

- client says which host

- we can route (happy ending)

But TCP is fairly not straightforward :

- client connects

- …

- …

- …

And there comes TLS SNI extension. Basically, SNI happens when you’re connecting to a TLS service and essentially happens during the Client Hello (first message). The client can tell the server which domain he is currently trying to reach.

OracleInstancedChallenge

OracleInstancedChallenge are pretty much the same (but different). Some challenges can’t have winnable flags due to their nature (or else it wouldn’t feel very realistic).

Hence, we created Oracle Challenges. I’ll explain with an example :

We had a challenge called Plz Help Me that was here to introduce our notion of what a “Blue Team” challenge could look like.

The challenge tells you the following :

My friend said that his server is restarting every 10 minutes. He isn’t able to find the issue. Can you help him?

What you have to do is simple, find the cron, script or whatever, delete it and boom solved. Now, where would you put the flag?

The challenge has some kind of a state, solved or not, and we can verify that state thanks to a script : «is the malware still there?»

And that’s exactly what we added to the previous example :

oraclePort:

route: /is_solved

pod: main

port: 5000With this, we have a route that checks if the challenge is solved or not, and can detect if the player should earn their points or not.

GloballyInstancedChallenge

GloballyInstancedChallenge are InstancedChallenge, without timeouts, and only an administrator is be able to instance them, the goal is to keep the same logic between InstancedChallenge and GloballyInstancedChallenge

We ended up not using those because we didn’t have time to properly test them out :(

API

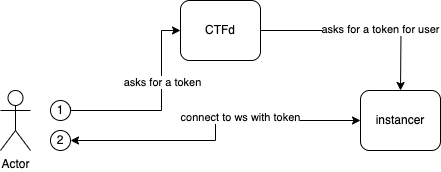

Our instancer also provides an API with some useful endpoints for the CTF platform and/or to the player.

We had routes to manage instances of challenges so that the platform does not have to keep track of them and it also handled killing instances that reached their time out.

We also had a route (for CTFd) to generate a token for players to allow them to connect directly to the instancer and receive events, it worked a bit like this :

This websocket is used to notify players on instance status to avoid polling for the information, though, it also is possible to roll back to polling if necessary.

The final route we had was to verify an Oracle instances status. It was just a glorified proxy to the route we saw earlier defined in the challenge’s ressource.

CTFd

The instancer also has a CTFd token, and that’s very useful to synchronise the cluster with the CTFd.

Basically, when a challenge as either created, modified or deleted, the reconciliation loop had to query CTFd to find the challenge, verify that it’s the same (files, hint, flag all that stuff) and modify it if it is necessary.

This step should definitely be improved upon, it was especially slow when we had a lot of challenges.

CTFd plugin

For this magic 🪄 to work, we also had to add features to CTFd (to handle instanciation, token generation and oracle challenges).

All I had to do was copy CTFd’s “dynamic challenge” plugin, and modify it to add our logic in there. I ended up doing this for the database model :

id = db.Column(

db.Integer, db.ForeignKey("challenges.id", ondelete="CASCADE"), primary_key=True

)

initial = db.Column(db.Integer, default=0)

minimum = db.Column(db.Integer, default=0)

decay = db.Column(db.Integer, default=0)

function = db.Column(db.String(32), default="logarithmic")

slug = db.Column(db.String(32))

is_instanced = db.Column(db.Boolean, default=False)

has_oracle = db.Column(db.Boolean, default=False)And I also added some awfully looking JS to make the plugin work on CTFd default theme (that way we can use it after the CTF has ended if we encounter some issues)

It also included the check for oracle challenges which was really simple to do : I modified the “attempt” function that normally takes in an input as well, and change it’s behaviour if the challenge was an oracle challenge. That fancy talks means that we can simply hide the input, and use the same button that’s already present on our custom theme :D (and change the styling of course)

Kall

Kall is the first challenge we decided to design on our infrastructure, with out own contraints and with our own instancier (i)

We probably should’ve given a name to our infrastructure (not

idue to conflict). If I were to name it after the fact, I’d name itflipsince it flips instances for the players. Also “être flipper” in French means “being scared”, so that would rightfully represent our mental state right before the beginning.

Kall was meant to be a supercharged challenge, that uses more resources than a typical challenge and that takes a bit longer to solve due to its nature.

We also chose to make Kall into some sort of simple challenges with 4 steps (4 different flags) so that the people who are trying it (first year’s students) would not get lost.

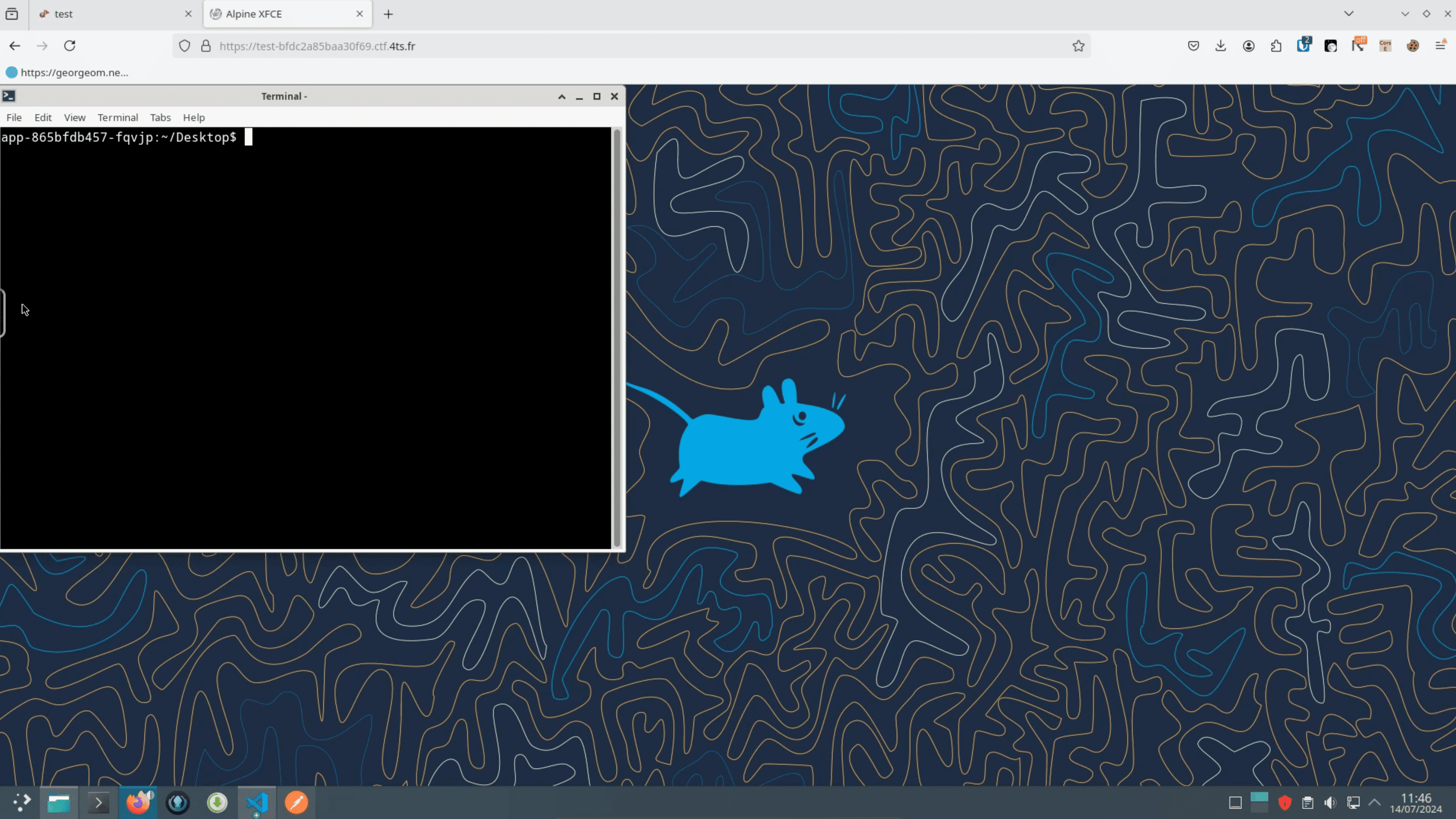

Essentially, Kall uses a modified webtop and allows the user to play, on their browser, thanks to a Web VNC (KasmVNC).

The four parts of the challenge are the following :

- Find a dot file on the Desktop (which are hidden by default)

- A git repository with compromise secrets in its history

- A process that leaks information in its arguments

- A protected zip file with Chef instructions inside of it

It was not meant to be hard (other than the Chef part), but it allows us to test our infrastructure and have a lot of fun while doing so.

Of course, here’s a sneak peak of what Kall looked like for the players :

We ended up lending these resources to each instance :

- 0.85 CPU

- 700 MB RAM

We also used our metrics to analyze what was going on during the test, and got pretty happy with the results, meaning we could go on. Overall satisfaction was good and the players also really liked the challenge, it was our first step to publicly announce our CTF and to show that we were working hard towards our goal.

Challenges

Then, comes the most challenging part, pun intended.

For this, I ended up choosing gitlab.com over github.com for its flexibility when it comes to permissions.

We had this kind of organisation:

4T$

└── CTF 2024

├── Web

│ ├── Example

│ ├── Challenge 1

│ └── Challenge 2

├── Crypto

│ ├── Example

│ ├── Challenge 1

│ └── Challenge 2

├── Reverse

│ ├── Example

│ ├── Challenge 1

│ └── Challenge 2

├── ........

│ ├── Example

| ├── Challenge 1

| └── Challenge 2

├── CI

│ └── Components

└── Authors (no subrepo, only members)

├── Alice

├── Bob

├── Carol

└── DavidThis helped a lot to control which Author had access to what, for example if you wanted to create a web challenge, we would add you to the author list. This group had access to every “example” challenge (to avoid us filling that in), and then we would add you to your repo for your challenge. This way you had the knowledge of every category done so far, and how to populate your own repository following the guidelines in the example challenges.

Next year, we plan on going further and creating actual templates (not just examples) that you must abide to when creating a challenge, another task is to simplify the

chall.ymlfile that describes the challenge to our instancer though it seems harder for us to do right now.

We planned on getting most of the challenges ready the week before the event, however some challenges didn’t make the cut, and some other were done somewhat during the last week (which is a bit of a frustration when you also need to prepare the infrastructure during that time)

We also planned on releasing the challenges in 2.1 waves, the first one being on the opening day, the second one on the Saturday at 4 PM and one more challenge on Sunday morning.

The worst one probably was Homelab Pwnlab (the name will come back later), which was officially done (and tested) 15 hours AFTER the beginning of the event..

I also worked on some challenges:

The main one being the Fil Rouge which is a series of challenges involving a scenario and is available on our public gitlab project.

Most of the example challenges (that we kept private) and onboarded author when they were doing their challenges.

Blockchains challenge were also a pain in the ass, for them, I wanted to avoid using a Proof of Work algorithm, which heavily relies on ressources available, and instead opted for a testnet using Proof of Authority divided in three parts so that the user can access an already opened wallet without compromising the “admin” wallet. This was really fun to experiment with and most people were happy with what we’ve done. The project is also public.

I also worked on miscellaneous challenges that revolve around a false casino bot on Discord. It was a way to explore Discord’s API and predictible PRNG.

Finally, I worked on the 3 web challenges available during the CTF:

- are you sane (an introduction and sanity check)

- sky blog

- homelab pwnlab

Homelab Pwnlab is a multilayered challenge because it involve exploiting a web application and then exploiting the machine it runs on. The exploitation technique is well explained in the writeup, and if you only wanted to check one out, I’d consider this one :D

Now, automation, here’s what happens when we (an admin) tags a challenge :

- (optional) Build the Dockerfile(s)

- Send a commit to a GitHub Repo

This is a funny part because we have a Github repository with every deployment files (has the same folder structure as our gitlab organisation) to simplify the deployment to the clusters.

On the Github Repo, every push triggers an action that deploys everything to our cluster, meaning that we can easily change which cluster it is deploying on without having to go through every challenges :D

Automations

Furthermore, and contuining on the topic of automation, we also had to simplify our workflow when dealing with the CTFd platform.

For this matter, we had three Github Repos :

Github

└── 4T-24

├── ctf-2024-ctfd

├── ctf-2024-ctfd-theme

└── ctfd-instancier-pluginHowever, to be completely built, CTFd requires to have the theme built and placed at the correct spot on the image, and the same applies for the plugin.

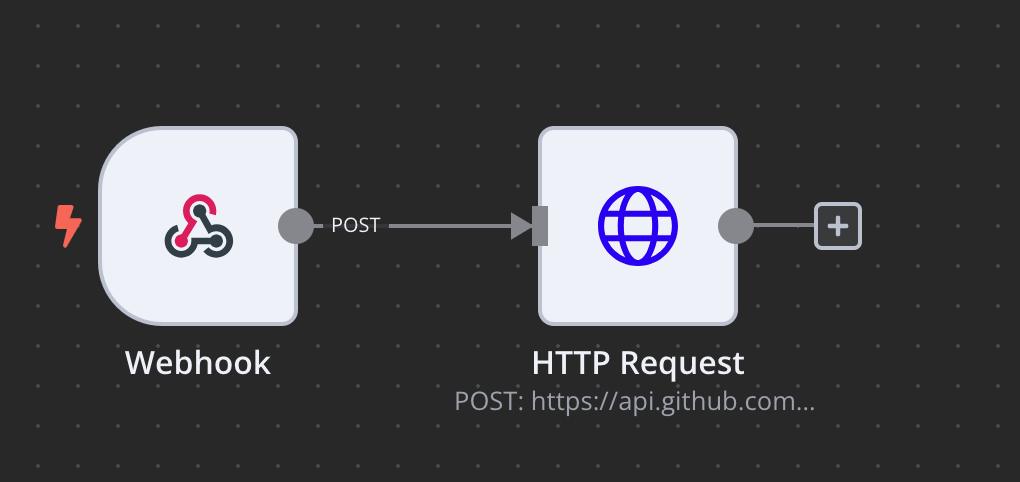

To do this, I set up webhooks when commits were added on either the theme or the plugin and this webhook was pointed to my personnal n8n instance. The workflow then triggers the CI for the CTFd that can update its theme and/or plugin. After the build process, we would then push the image to our test environment. The workflow in n8n looked like this :

This was not auto deployed to production, and I manually updated if it was necessary during the event.

Before the event

I installed the production infrastructure on the Thursday right before the event with 46 workers, 3 control planes and 1 load balancer for the control planes. Here’s an extract of the variables I used :

control_plane_image_id = "Debian 12 bookworm"

control_plane_flavor_id = "a4-ram8-disk20-perf1"

control_plane_number = "3"

worker_image_id = "Debian 12 bookworm"

worker_flavor_id = "a4-ram8-disk20-perf1"

worker_number = "46"

load_balancer_image_id = "Debian 12 bookworm"

load_balancer_flavor_id = "a2-ram4-disk20-perf1"In total, this represents 200 vCPUs, 400 GB of RAM and around 1 TB of storage.

I also chose to create another machine, solely for CTFd and moved the one we were using for the registrations [which was somewhere on one of my servers before that].

The final part of the setup was moving some DNS stuff around, this was done 2 hours before the beginning to account for propagation and fun caches that often are weird enough to generate issues.

The event

As the clock ticked towards 7 PM, time seemed to slow down; we were all patiently waiting for the competition to start.

Then, the first messages started rolling in—reports of instances being down, along with rumors that downloads were failing too. The latter turned out to be just a rumor, but we were indeed having issues with the instancer, and they seemed disturbingly random.

After some intense debugging, we discovered that when generating a new token for communicating with the WebSocket, I had also stored the URI of the instancer. Since players could generate tokens before the CTF began, they ended up with tokens meant for our test environment in their local storage. This resulted in their instance states becoming a confusing mix between the test and production environments.

Although the fix itself was straightforward, it required participants to clear their local storage. After handling several support tickets, we decided to take down the WebSocket entirely and revert to our polling method—nearly two hours after the event had started. This move resolved the instancing issues for most users, allowing the infrastructure to handle the incoming requests.

Later (albeit a bit late), we realized we’d forgotten to update the styling for the Oracle Challenges, leading players to mistakenly submit flags there. Fortunately, this was a quick fix, which we applied around 11 PM.

In the meantime, we also provided hints for particularly tough challenges and updated a few challenge descriptions. I finally signed off at around 1 AM, ready to be back by 8 AM, when things seemed to have calmed down.

On the second day, our main goal was to make Fil-Rouge more approachable by adding hints and tweaking some challenge files.

When prepping for the second wave of challenges, we faced a peculiar issue with a challenge where i was acting up. After some head-scratching, I pulled the challenge from production to test it in our environment. Turns out, I had overlooked the 32-character limit on the slug for challenges—a subtle bug caused by a slug that was exactly 34 characters long! After an hour of debugging, I resolved it just in time to push out the second wave at around 4:04 PM.

This new wave exposed another hiccup with Homelab Pwnlab: an unintended solution had emerged that made the challenge too easy, and instances were slow. We quickly fixed this by changing the flag file permissions and upgrading its CPU and RAM. We also asked the three teams who’d solved it if they were okay with resetting their flags until they had the intended solve. To their credit, all three teams were great sports; one even went on to claim first place!

After that, things went smoothly. With no further technical issues or ticket floods, we could relax till the end…

However, during the final stretch, someone tried to contact a friend of us asking for a flag (which is basically cheating) and that friend of us warned us about this since the person was also using a second Discord account. We came up with a good idea to trap him and asked to our friend : «Ask him a trade, you give him a hint (that we give you) and he gives you a hint as well». We tasked him to tell him about a second bridge that looked just like what he was looking for, and also that nobody else tried. Then, by checking the submissions on CTFd, we could figure out who asked for the advice… Turns out it was a member of the 4th team, that promptly got banned and nuked to 12th place. The other members were not even playing so it also came as a surprised for them.

The last thing to do was figure out how to export our scoreboard for CTF Time, and I tested it before ending the CTF, so that was handled as well.

After the event

Then, we chose to keep the challenges open and instanciation open as well, to let people finish their writeups and stuff like that. We announced the winner and everyone seemed to have enjoyed our little CTF.

Statistics

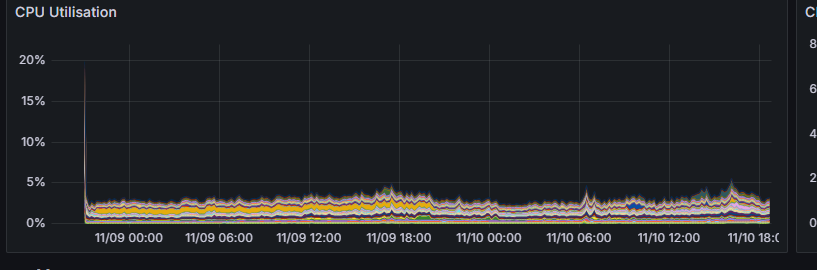

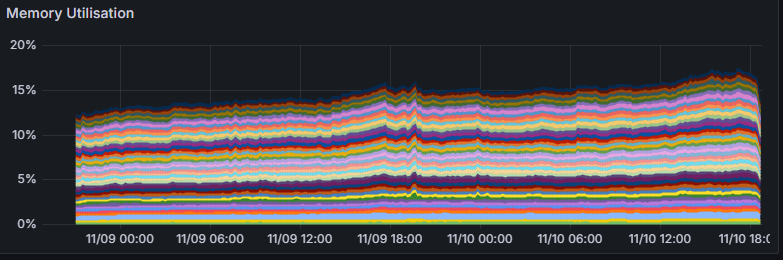

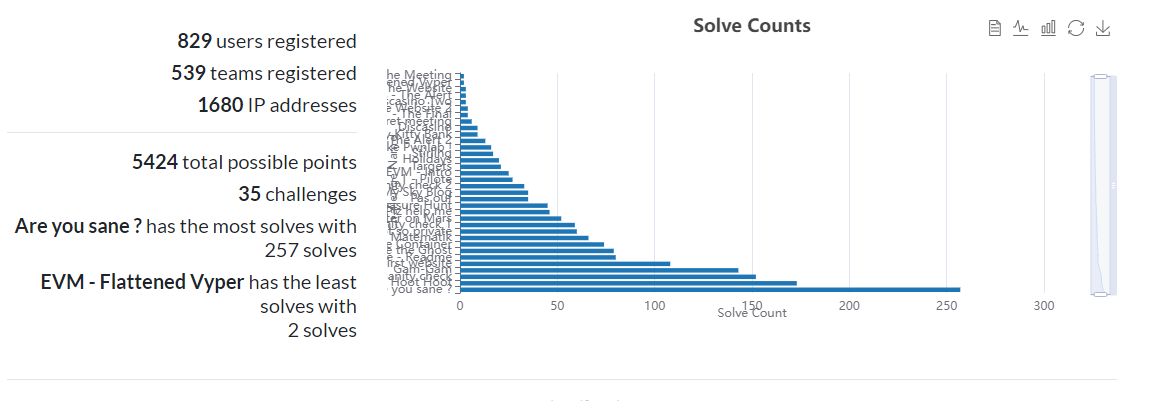

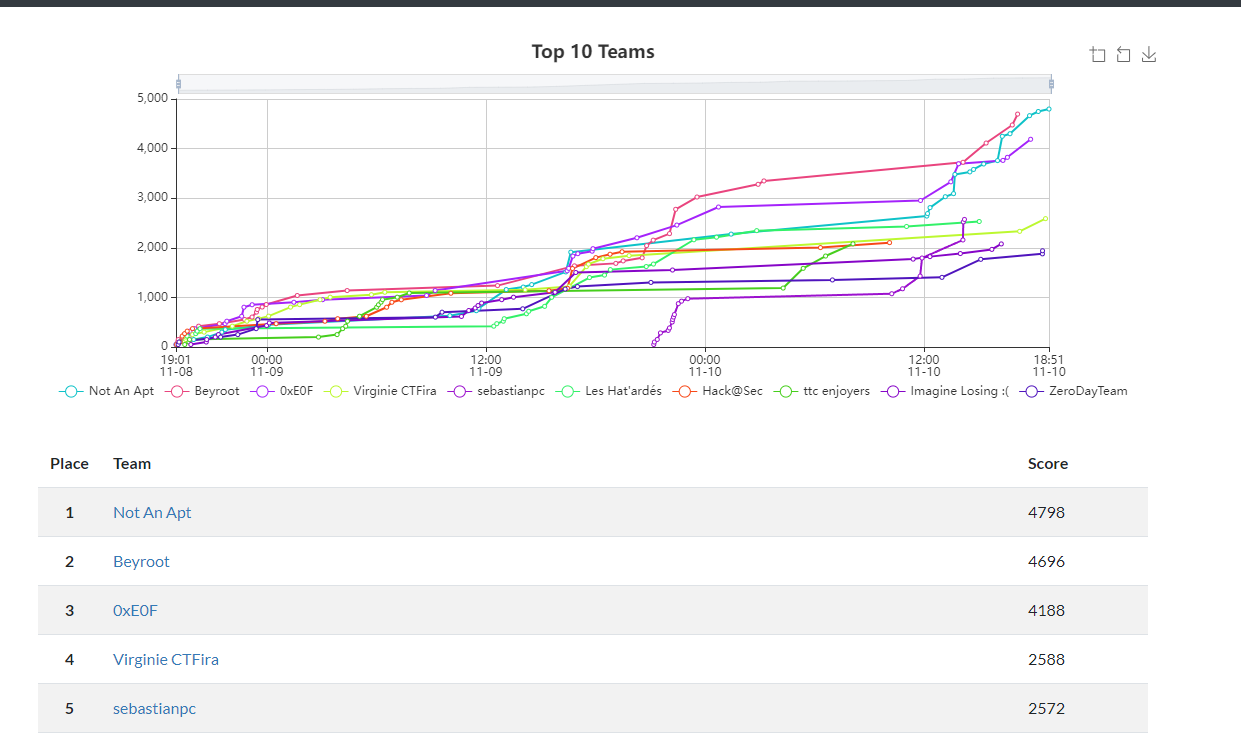

During the CTF we recorded every data we could. So here’s some graphs you may enjoy :

On this one we can see quite a spike at the very beginning, which could explain the slowness we experienced for a short while.

Memory usage was pretty much not impacted at all

EVM Flattened Vyper was a notoriously hard challenge for most people who weren’t used to Blockchains challenges.

This is the final scoreboard, with the winners !

Conclusion

Overall, this CTF was an incredibly rewarding experience for me, both technically and personally. Throughout the weekend, I had a great time engaging with participants, exchanging insights, and exploring some impressive write-ups people shared. Seeing how players tackled our challenges, and hearing their feedback firsthand, brought the event to life in a way I hadn’t anticipated.

For a first edition, I think we did an outstanding job. Despite being a small team, we pulled off a unique, well-rounded experience that left a memorable impact on players. From our creative challenges and technical setups to the organization that kept everything running smoothly, we managed to bring some originality to the table.

Looking back, I’m proud of how we handled the technical hurdles and the unexpected twists. Each fix, from dealing with instance issues to patching challenge bugs, taught us something new about scaling and resiliency in a real-time event. Beyond the technical aspects, this experience was also quite an enriching human experience.

I’m excited to take everything we learned and push even further next time. Here’s to more innovation, collaboration, and, of course, a few surprises along the way!

I also am looking forward to using Kubernetes As A Service from Infomaniak next year in order to spend more time developing stuff, and less time worrying about the infrastructure as a whole (even though it’ll probably still be my job :D)